THIS INSIDE UKRAINE STORY IS FROM AN UNDISCLOSED LOCATION.

* All images and answers in the feature were provided by the WOW Woman, unless otherwise specified.

INSIDE UKRAINE SERIES: A SNAPSHOT, A DAY-IN-THE-LIFE, A GLIMPSE OF WHAT IT’S LIKE TO LIVE, RESIST, SURVIVE AND PERSEVERE IN A NATION UNDER ATTACK.

GLORY TO THE UKRAINIAN WOW WOMEN, FOR SUPPORTING THEIR COUNTRY AND BRINGING UKRAINE CLOSER TO VICTORY.

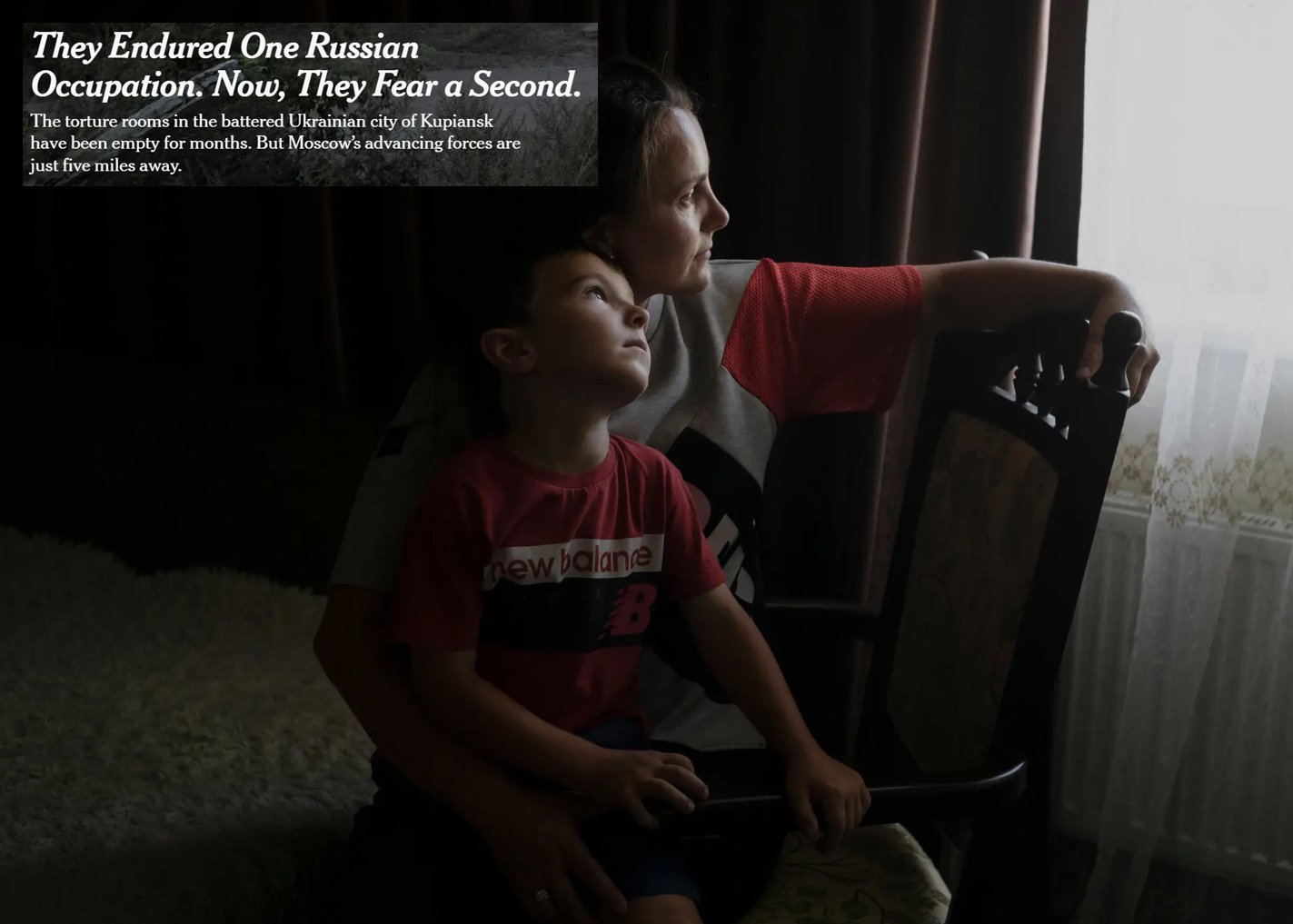

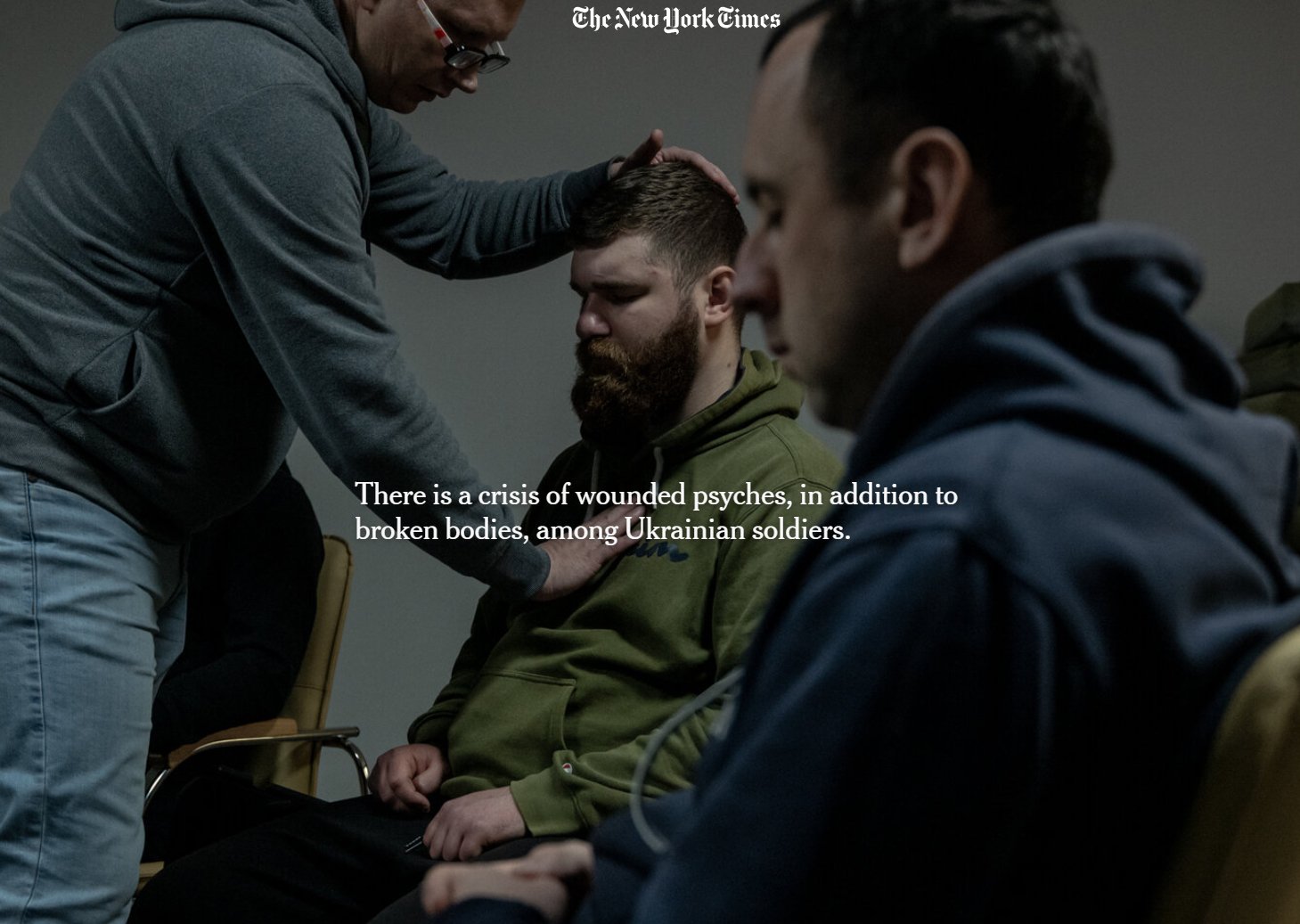

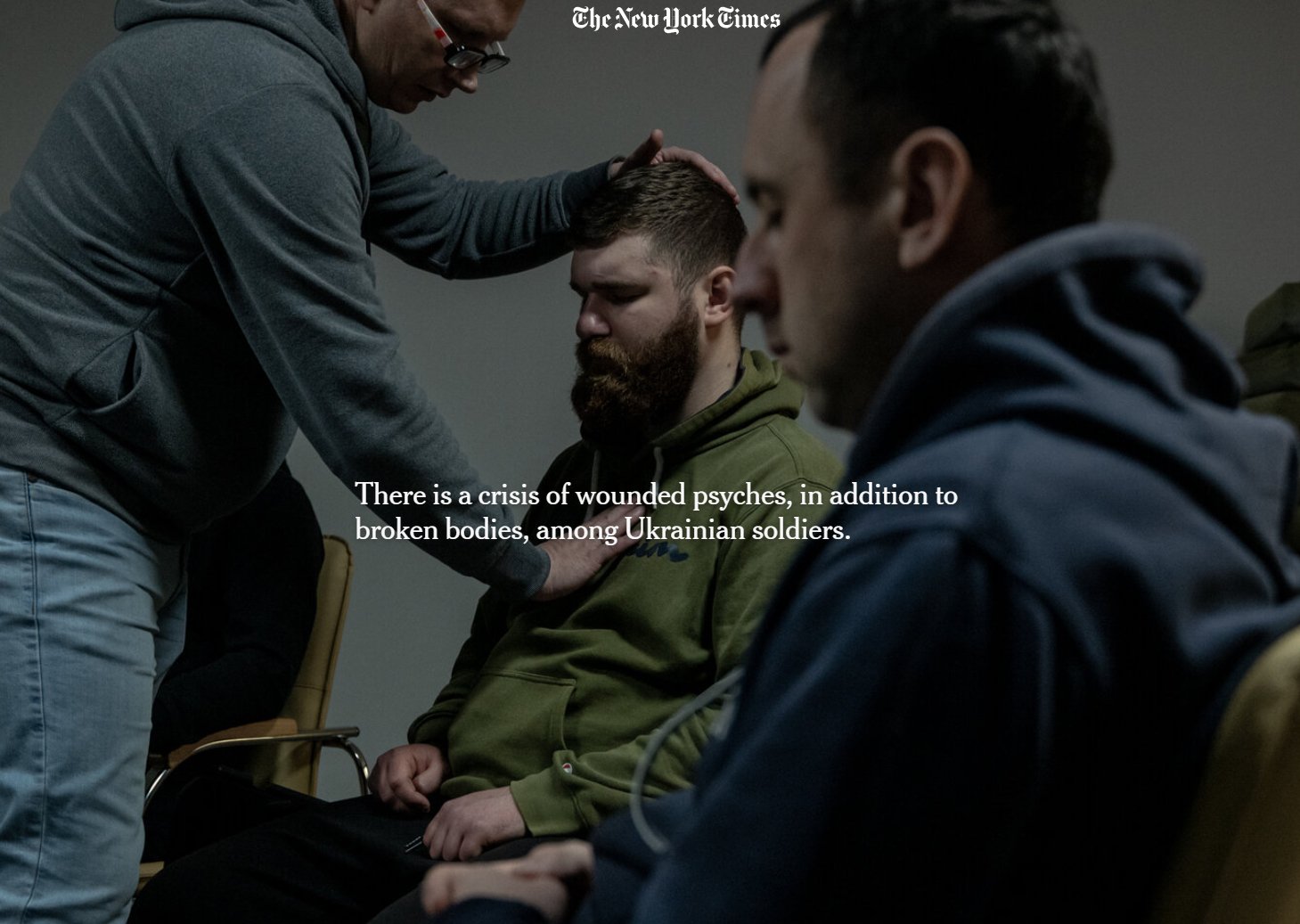

Ukrainian women continue fighting for their country, displaying courage, perseverance, and resilience in the face of russian attacks, invasion and occupation. As of this writing, russia’s war in my country has entered its third year, twenty-seventh month, and 813th day. Today’s New York Times headline warns of the imminent attack on and attempt to take Ukraine’s second largest city, Kharkiv. My resolve to write about brave, defiant Ukrainian women is stronger than ever; that’s because women like my Inside Ukraine WOW Woman keep persisting. Because of my WOW Woman’s actions, millions are able to better understand the reality of russian atrocities in Ukraine.

Foreign correspondents covering russia’s war in Ukraine may not know the language nor the local customs, so they rely completely on competent Ukrainians, often referred to as “fixers”. Fixers arrange and sort out every single detail for foreign correspondents and photographers. Working as a fixer can be quite dangerous because fixers move towards conflict zones instead of running away. Additionally, fixers serve as the face of the locals to the foreigners and vice versa, which at times creates friction and may pose dangers to both parties. At the end of the day, journalists get their stories and leave, but fixers stay behind, with the local population in the ruins of the war.

I was able to interview a Ukrainian fixer for the New York Times, Ms. Evelina Riabenko. Needless to say, she is an incredible WOW Woman who traverses heavily bombed areas of Ukraine with multiple crews of photographers and journalists. Ms. Evelina Riabenko possesses the boldness and bravery to embed with military personnel, earn locals’ trust, and translate the pain of loss as well as the horrific accounts of russian torture and sexual assaults. By risking her life daily, Ms. Riabenko aids in exposing russian barbarism to the global audience.

To date, Ms. Riabenko’s professionalism has contributed to over 50 stories for the New York Times. After reaching out to several Times colleagues, I realized why they keep hiring her: to know Evelina is to love her. She possesses an indomitable spirit and pure, defying all expectations, joy. Like most Ukrainians in the past two years, Evelina found herself in a completely different life role. She hails from the severely bombed eastern region of Ukraine, where she studied engineering and completed a Master’s Degree in large machinery building. When russia invaded sovereign Ukraine, Evelina was working in human resources at a railroad company; the New York Times was farthest from her mind. But russia’s war in Ukraine brought out heroic actions from regular Ukrainians, and Evelina decided to use her skills optimally to help her homeland. She conveys and translates people’s stories to the world’s top journalists who, in turn, disseminate the truth about russian aggression. However, what I admire most about Evelina is her courage to really listen to her countrymen, help them unburden, and feel heard. To me, this is Evelina’s true superpower.

I extend my deepest gratitude to both international and local photojournalists as well as their Ukrainian fixers who continue to document russian invasion and share the truth with the world. I firmly believe that storytelling, whether through visual imagery or personal narratives, serves as a form of justice. I endeavor to contribute to the effort of documenting the stories of people who are living and persevering through this horror.

- Olga Shmaidenko, Founder of WOW Woman.

Above stories resulted from a collaboration between professionals at The New York Times, Evelina Riabenko and other incredible Ukrainians, all willing to risk their lives in order to expose the truth about the russian invasion of Ukraine and the aftermath of the russian atrocities on Ukrainian soil. To date, Evelina Riabenko is credited as a collaborator on over 50 articles for the Times.

PHotographer Nicole Tung shared the following about Evelina Riabenko’s professionalism and work ethic:

“From day one, Evelina has brought a kind of tenacity to her work ethic that is rare, and she does so with a great deal of grace. That’s probably how I’d best describe her: as someone who works with grace under extreme pressure. As someone who has to always be multitasking - making phone calls, establishing relationships, staying on top of what’s being organized, understanding the movements in a fluid situation such as this war, translating, understanding what photographers and journalists want, the list goes on.

Evelina is the best operator I’ve worked with and her charm and wit through it all are remarkable. Evelina witnessed horrors from the early days of the war - her first assignment was to uncover the atrocities in Bucha - and she has relentlessly followed every twist and turn in a grinding conflict, with the belief that getting these stories out mattered then and matters still.”

- Nicole Tung, a photojournalist covering russia’s war in Ukraine for The New York Times.

Photographer Brendan Hoffman shared the following about Evelina Riabenko:

“Evelina is a dream colleague. Most importantly, she's good at what she does. She thinks three steps ahead but is also quick to seize surprise opportunities, all with a keen understanding of how to balance the narrative aspect of journalism with the need for visual interest, which is so critical for a photographer. If that weren't enough, I've never seen her in a bad mood! She is relaxed when possible, focused when necessary, and easy to be around, even when everyone else is tired and grumpy. Long story short: I trust her, and so do many other colleagues, which I think is the ultimate compliment.”

- Brendan Hoffman, a photojournalist covering russia’s war in Ukraine for The New York Times.

Fixer, Freelance Producer, Ray of Sunshine, Translator, Logistics Guru, Undisclosed Location

3. What did you study and what is your profession?

I graduated from Donbas State Engineering Academy with the goal of becoming engineering technologist.

4. What was your typical day like before the war and how has your role changed since the invasion of Ukraine?

Before the war, I used to wake up at 6:30 AM, go to the gym, then to the office and eight hours later I had dinner at home. Now, I don’t know how to describe a typical day because with journalists you have no typical days. Absolutely everything is unpredictable and things can changed by the hour. A day can start at 8:00 AM (as for other normal people) or it can begin at 2:00 AM, when I find myself travelling to the positions on the war’s front line.

Evelina. Life, before and after. Images provided by Evelina Riabenko.

How did you get into your current role?

In March 2022, at the start of the russian invasion, my husband and I left Kyiv, seeking safety, and travelled to a tiny village. I was going stir-crazy there because I’m a city person. On March 31, 2022, I received a call from a friend who was working in media, helping various NGOs, since the start of the russia-provoked 2014-2015 war in the Ukrainian region of Donetsk. She suggested I try and work as a translator because there were thousands of journalists in the country but not enough English/Ukrainian translators. At that time, Spanish journalists were looking for someone, would I be up for trying? I didn’t know what to do because as I mentioned I knew nothing about journalism. I decided with my friend, that I would try. She gave me numbers of 10-15 contacts and wished me luck.

Unfortunately, my first experience working with foreign journalists involved covering russia’s atrocities in Bucha (a small suburb of Kyiv which was occupied by the russian forces) on April 3, 2022. That was truly horrible. The first interview was with Father Andriy, an Orthodox priest who led services near the site where russians left a mass grave. He was patiently telling me what happened there and I was supposed to translate. His words paralyzed me, I was so shocked that I couldn’t continue my translation.

After two weeks of working as a translator for various newspapers, I was introduced to the New York Times photographer, again in Bucha, at the cemetery during a funeral. After April 2022, I have been working for the New York Times exclusively.

5. What would you say are your strengths and superpowers?

Natural curiosity, restlessness, willingness to communicate and readiness to gamble.

(Images provided by Evelina Riabenko)

6. What are some concrete actions (big or small) you’ve done and continue doing to help Ukraine and Ukrainian people?

In my opinion, praising oneself is wrong. I don’t do this (help people) for the glory! That’s why don’t like to talk about it. I’ve helped Ukrainian civilians with evacuations and aid, just as thousands of other Ukrainians have done.

I work as a freelance producer for a big newspaper with a global readership. We try to show the reality of the cruel war in Ukraine to the entire world and maybe this somehow helps attract attention to our tragedy and get support, donations and empathy to Ukrainians. I truly hope that my job helps my country.

On an assignment in east Ukraine. Images provided by Evelina Riabenko.

7. What are things you do just for you? Is it possible to stay sane in a war situation? What are some things that help you to not lose yourself?

Taking some breaks in my schedule, walking a lot and believing that everything will turn out alright. There are thousands of people in Ukraine surviving through much worse situations. I constantly keep this in mind and try not to complain.

On an assignment in east Ukraine. Images provided by Nicole Tung.

8. Do you feel the war changed you? How? Since the start of the war, has anything surprised you about yourself (how you have handled yourself, remained strong, found inspiration in unlikely sources, etc.), about your country, about your ideas about humanity? What have been some of your epiphanies?

Unfortunately yes. I see that I’m not as cheerful and carefree as I used to be; I don’t laugh as often as before. At the same time, I know that we shouldn’t give up, it’s our life and reality and we have to keep living. I believe that if I get stuck with negative thoughts for too long, depression will soon follow.

I’m quite used to this reality and the frontline work. I’ve gotten better at emotional self-control. I’ve become grateful for my life and simple things like waking up in my bed, having nice coffee and being in a peaceful setting bring me happiness. I admire Ukrainian people, they’re fantastic, brave, smart and don’t even think about giving up (at least the ones who I know).

9. What do you want the world to know about Ukrainians at this moment in time? About Ukrainian women?

Ukrainian women are the treasure of Ukraine! They’re brave to fight at the front, they’re wise to support their military loved ones, they’re kind to help other Ukrainians in need. Ukrainian women volunteer, donate and help others evacuate; they’re strong enough to continue living life while taking care of their children, as single mothers (unfortunately Russia has eliminated/killed many of our brave defenders). Our women are real guardians of their families and won’t let anyone hurt them.

On an assignment in east Ukraine. Images provided by Evelina Riabenko.

10. What are some difficulties with being a fixer, producer of stories, a person in the middle who can communicate with both sides - Ukrainians and the journalists?

It can be tricky because either side may blame the producer when something goes wrong. The most difficult part for me though is when we interview people and it’s me whom they tell the story, not the journalists. They look at me because of the shared language and sometimes it’s really tough to pass that pain and tears. These emotions do pass through me.

11. Is it difficult to live in Ukraine and try to reach a foreign audience? What is the most difficult aspect? And the most positive?

It’s becoming increasingly difficult every day. News get outdated quickly and keeping foreign attention on Ukraine is challenging. We have to find more interesting stories, facts, evidence and so on. Ukraine is not the top story in the world, unfortunately. Foreign audiences see it as, “oh, Ukraine … again!” Despite everything, journalists are in love with Ukraine. They keep coming back, wanting to work here and keep talking about what is happening here. They clearly understand the situation on the ground and do their best to attract readers’ attention.

12. Who are your WOW Women who inspire you?

WOW Women for me are those who are brave enough to fight for our independence at the front, shoulder to shoulder with the men. Ukrainian WOW women are fighting and get respect from their comrades, they don’t give up. They inspire me very much as I confess, I’m not as brave as them.

“A former lawyer whose call sign is Witch commands a Ukrainian artillery platoon from the 241st Brigade.” Photographs and text by Nicole Tung. Evelina Riabenko contributed reporting. March 10, 2024. The New York Times.

13. What is a place or activity that makes you feel happiest?

A pretty simple thing makes me feel calm and happy: walking thousand of steps with a cup of coffee in an interesting surrounding.

14. How do you see dynamics changing inside the country, with attitudes toward those who left vs those who stayed? Do you think that Ukrainians who left the country have a specific responsibility toward their homeland?

To be honest, I don’t think that those who left the country have a special responsibility. It was their choice. They’ll live with this choice for the rest of their lives. We don’t have the right to judge them.

But if you left, please do help somehow, at least with donations; don’t show us, the Ukrainian military, the world your perfect life in a safe and fancy place. It hurts many people and triggers them. If you’re asking about the situation inside the country it’s worse: it seems that people in not-combat regions have almost forgotten about the war. To them, the war is somewhere “there”, far from them.

The situation of 2014-2015 conflict seems to be on a repeat. Ukrainians won’t win living like this! Soldiers who return home on a leave see that people just don’t seem to care about the war. Meanwhile, Ukrainian soldiers are being killed at the front every day, for the rest of the country to have this peaceful life. Civilians must care more and pay attention.

15. How are you able to do what you do, how do you find the courage to be at the front and what keeps you returning to your job every time?

I believe I am helping somehow, it gives me courage to keep going.

Additionally, working with journalists is something truly unique - I’ve never before met so many interesting people, been to so many places inside my own country and abroad. In this line of work, you’re always ON and feel up-to-date; it might be some kind of addiction.

Nicole Tung, Evelina Riabenko and the team, working in various parts of Ukraine, showing reality of russia’s war in Ukraine to the world! Source: Evelina Riabenko’s Instagram stories.

16. What will be the first thing you’ll do when Ukraine wins? What are your dreams for yourself and your family after the war is finished?

Cry.

I now understand why our grandparents and great-grandparents cry when they talk about the Second World War. They say that there is nothing worse than the war, and they are right.

I don’t dream about the victory because I don’t wanna live inside dreams or illusions. The victory is too far to dream about our life after. We have to live today.

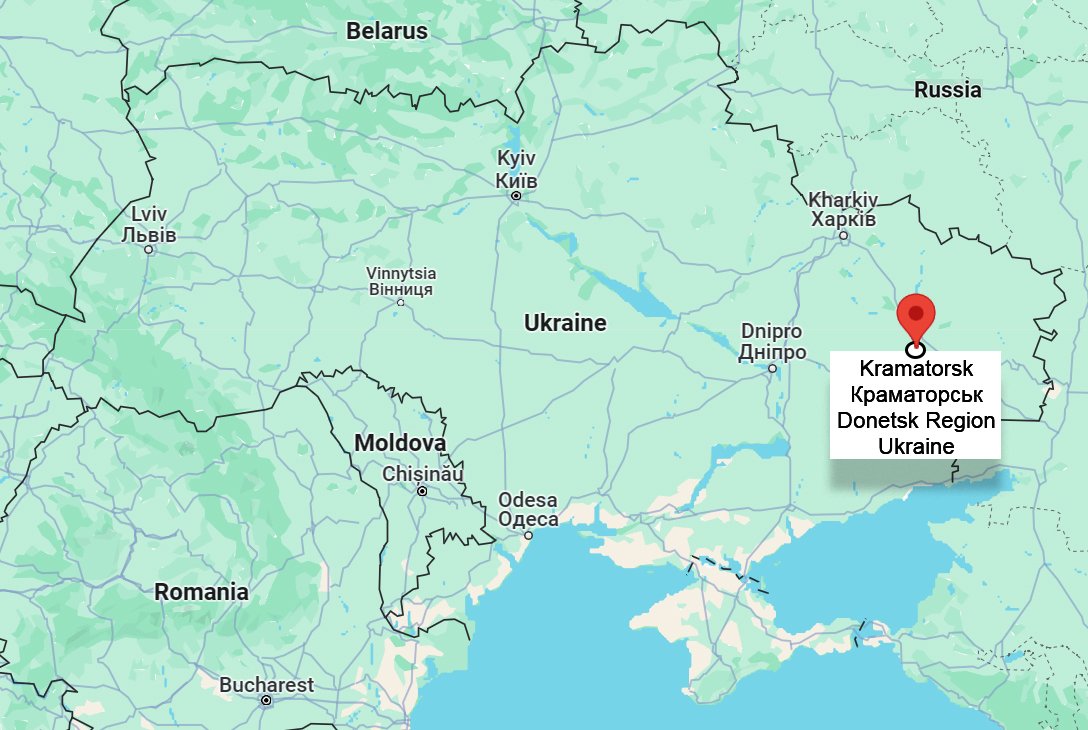

In front of the Kramatorsk (Ukr. Краматорськ), Evelina’s hometown, city sign. Photo provided by Nicole Tung.

17. Where can others find you/your work? (links to website, blog, etc).

My FB: @eveline.riabenko

Instagram: @evelineryabenko

The NYT website, where I helped put together stories like this one: “It’s a Way of Life’: Women Make Their Mark in the Ukrainian Army”. It’s about a surge of Ukrainian women enlisting and volunteering for combat roles.

This is my LInkedIn profile.

ЦЯ ІСТОРІЯ "INSIDE UKRAINE" - З ПЕРЕДОВОЇ.

* Всі фотографії та відповіді в матеріалі були надані WOW Woman, якщо вказано інакше.

СЕРІЯ INSIDE UKRAINE/ВСЕРЕДИНІ УКРАЇНИ: МОМЕНТАЛЬНИЙ ЗНІМОК, ОДИН ДЕНЬ З ЖИТТЯ, ПОГЛЯД НА ТЕ, ЯК ЦЕ - ЖИТИ, ЧИНИТИ ОПІР, ВИЖИВАТИ І НЕ ЗДАВАТИСЯ В КРАЇНІ, ЯКА ПЕРЕБУВАЄ ПІД ЗАГРОЗОЮ.

СЛАВА УКРАЇНСЬКИМ ВАУ-ЖІНКАМ, ЯКІ ПІДТРИМУЮТЬ СВОЮ КРАЇНУ І НАБЛИЖАЮТЬ УКРАЇНУ ДО ПЕРЕМОГИ.

Українські жінки продовжують боротися за свою країну, проявляючи мужність, наполегливість і стійкість перед обличчям російських атак, вторгнення та окупації. На момент написання цієї статті війна росії в моїй країні триває вже третій рік, двадцять сьомий місяць і 813-й день. Сьогоднішній заголовок New York Times попереджає про неминучу атаку і спробу захоплення другого за величиною міста України, Харкова. Моя рішучість писати про хоробрих, непокірних українських жінок сильніша, ніж будь-коли; це тому, що такі жінки, як моя героїня "Inside Ukraine WOW Woman", продовжують боротися за своє право на життя. Завдяки діям моєї WOW-жінки мільйони людей мають змогу краще зрозуміти реальність російських звірств в Україні.

Іноземні кореспонденти, які висвітлюють війну росії в Україні, швидше за все, мабуть не знають ні мови, ні місцевих звичаїв. Потрапляючи в зону бойових дій вони повинні повністю покладатися на компетентних українців, яких часто називають "фіксерами". Фіксери організовують і розбирають кожну дрібницю для іноземних кореспондентів і фотографів. Робота фіксером може бути досить небезпечною, оскільки фіксери не тікають, а їдуть у зону конфлікту. Крім того, фіксери є обличчям місцевих жителів для іноземців і навпаки, що іноді створює тертя і може становити небезпеку для обох сторін. Зрештою, журналісти отримують свої сюжети і їдуть, а фіксери залишаються, разом із місцевим населенням на руїнах війни.

Мені вдалося взяти інтерв'ю в українського фіксера New York Times, пані Эвелина Рябенко. Зайве казати, що вона неймовірна WOW-жінка, яка подорожує сильно бомбардованими районами України з численними командами фотографів та журналістів. Эвелина Рябенко має сміливість і відвагу входити в контакт з військовими, завойовувати довіру місцевих жителів і передавати їх біль втрати, а також жахливі розповіді про російські тортури і насильство. Щодня ризикуючи своїм життям, пані Рябенко допомагає викривати російське варварство для світової спільноти.

На сьогоднішній день професіоналізм пані Рябенко сприяв написанню понад 50 статей для New York Times. Поспілкувавшись з кількома колегами з "Таймс", я зрозуміла, чому вони продовжують наймати її: знати Евеліну - значить любити її. Вона має незламний дух і чисту, всупереч усім очікуванням, енергійність. Як і більшість українців за останні два роки, Эвелина знайшла себе в зовсім іншій життєвій ролі. Вона родом із сильно бомбардованого східного регіону України, де вивчала інженерію і отримала ступінь магістра в галузі великого машинобудування. Коли росія вторглася в суверенну Україну, Евеліна працювала у відділі кадрів залізничної компанії; New York Times була найвіддаленішою від її думок. Але війна росії в Україні призвела до героїчних вчинків звичайних українців, і Евеліна вирішила оптимально використати свої навички, щоб допомогти своїй батьківщині. Вона передає та перекладає історії людей найкращим журналістам світу, які, в свою чергу, поширюють правду про російську агресію. Але найбільше мене захоплює в Евеліні її сміливість по-справжньому вислухати своїх земляків, допомогти їм скинути тягар і відчути себе почутими. Для мене це справжня суперсила Евеліни.

Я висловлюю глибоку вдячність міжнародним та місцевим фотожурналістам, а також їхнім українським фіксерам, які продовжують документувати російське вторгнення та ділитися правдою зі світом. Я твердо вірю, що сторітелінг, чи то через візуальні образи, чи то через особисті розповіді, слугує формою правосуддя. Я намагаюся зробити свій внесок у зусилля з документування історій людей, які живуть і борються з цим жахіттям.

- Ольга Шмайденко, засновниця WOW Woman.

The New York Times Фотограф НІКОЛЬ ТАНГ РОЗПОВІЛА ПРО про Эвелину Рябенко:

З першого дня Эвелина проявила рідкісну наполегливість у своїй трудовій етиці, і вона робить це з великою витонченістю. Напевно, саме так я можу описати її: як людину, яка працює з витонченістю в умовах надзвичайного тиску. Це людина, яка завжди має бути багатозадачною - телефонувати, налагоджувати стосунки, бути в курсі того, що організовується, розуміти рухи в такій динамічній ситуації, як ця війна, перекладати, розуміти, чого хочуть фотографи та журналісти, і цей список можна продовжувати.

Эвелина - найкращий оператор, з якою мені доводилося працювати, і її чарівність та дотепність у всьому цьому просто вражають. Эвелина була свідком жахів з перших днів війни - її першим завданням було висвітлити звірства в Бучі - і вона невпинно стежила за кожним поворотом конфлікту, вірячи в те, що висвітлення цих історій було важливим тоді і залишається важливим досі.

- Ніколь Танг, фотожурналістка, яка висвітлює російську війну в Україні для The New York Times.

The New York Times Фотограф Брендан Хоффман так відгукнувся про Эвелину Рябенко:

Эвелина- ідеальна колега. Найголовніше, що вона добре знає свою справу. Вона думає на три кроки вперед, але також швидко використовує несподівані можливості, і все це з глибоким розумінням того, як збалансувати наративний аспект журналістики з потребою у візуальному інтересі, що є дуже важливим для фотографа.

Якби цього було недостатньо, я ніколи не бачив її в поганому настрої! Вона розслаблена, коли це можливо, зосереджена, коли це необхідно, і з нею легко бути поруч, навіть коли всі інші втомлені і сварливі. Коротше кажучи, я довіряю їй, як і багатьом іншим колегам, що, на мою думку, є найкращим компліментом.

- Брендан Хоффман, фотожурналіст, який висвітлює російську війну в Україні для The New York Times.

ФІКСЕР, ПРОДЮСЕР-ФРІЛАНСЕР, ПРОМІНЬ СОНЦЯ, ПЕРЕКЛАДАЧ, ГУРУ ЛОГІСТИКИ, МІСЦЕЗНАХОДЖЕННЯ НЕ РОЗГОЛОШУЄТЬСЯ

1. Ім'я.

Эвелина Рябенко.

2. Де ви народилися і де живете зараз?

Я народилась у місті Краматорськ на Донеччині. У серпні 2021 року переїхала до Києва.

3. Що ви вивчали і хто ви за професією?

Я закінчила Донбаську державну машинобудівну академію за спеціальністю "інженер-технолог".

(фото Ніколь Танг)

4. Яким був ваш звичайний день до війни і як змінилася ваша роль після вторгнення в Україну?

До війни я прокидався о 6:30 ранку, відправлявся в спортзал, потім в офіс, а через вісім годин вечеряв удома. Зараз я не знаю, як описати типовий день, тому що з журналістами не буває типових днів. Абсолютно все непередбачувано і все може змінюватися щогодини. День може початися о 8:00 ранку (як для інших нормальних людей), а може початися о 2:00 ночі, коли я їду на позиції на передовій.

До і після. Фотографії надані Эвелиною Рябенко.

Як ви опинилися на цій посаді?

У березні 2022 року, на початку російського вторгнення, ми з чоловіком виїхали з Києва в пошуках безпеки і поїхали в крихітне село. Я божеволіла там, бо я міська людина. 31 березня 2022 року мені зателефонувала подруга, яка від початку спровокованої росією війни 2014-2015 років у Донецькій області працювала в медіа, допомагаючи різним громадським організаціям. Вона запропонувала мені спробувати попрацювати перекладачем, бо в країні були тисячі журналістів, але не вистачало перекладачів з англійської/української. У той час іспанські журналісти шукали когось, чи можу я спробувати? Я не знала, що робити, бо, як я вже згадувала, нічого не знала про журналістику. Ми з подругою вирішили, що я спробую. Вона дала мені номери 10-15 контактів і побажала удачі.

На жаль, мій перший досвід роботи з іноземними журналістами був пов'язаний з висвітленням звірств росіян у Бучі, 3 квітня 2022 року. Це було справді жахливо. Перше інтерв'ю було з отцем Андрієм, православним священиком, який проводив служби біля місця, де росіяни залишили масову могилу. Він терпляче розповідав мені, що там сталося, а я мала перекладати. Його слова паралізували мене, я була настільки шокована, що не могла продовжувати переклад.

Після двох тижнів роботи перекладачем для різних газет мене познайомили з фотографом New York Times, знову ж таки в Бучі, на кладовищі під час похорону. Після квітня 2022 року я працюю виключно з New York Times.

Ці знімки Эвелини надала Ніколь Танг.

5. Що б ви назвали своїми сильними сторонами та суперздатностями?

Природна допитливість, непосидючість, бажання комунікувати та готовність до азарту.

6. Які конкретні дії (великі чи малі) ви зробили і продовжуєте робити, щоб допомогти Україні та українському народу?

На мою думку, хвалити себе - це неправильно. Я роблю це (допомагаю людям) не заради слави! Тому не люблю про це говорити. Я допомагала українському цивільному населенню з евакуацією та допомогою, як і тисячі інших українців.

Я працюю позаштатним продюсером у великій газеті з глобальною читацькою аудиторією. Ми намагаємося показати реальність жорстокої війни в Україні всьому світу і, можливо, це якимось чином допомагає привернути увагу до нашої трагедії і отримати підтримку, пожертви та співчуття українців. Я щиро сподіваюся, що моя робота допомагає моїй країні.

Деякі з історій Эвелина допомагала створювати і брала участь у написанні статей для Нью-Йорк Таймс.

7. Що ви робите тільки для себе? Чи можливо залишатися розсудливим у ситуації війни? Які речі допомагають вам не втратити себе?

Робити перерви у своєму графіку, багато гуляти і вірити, що все буде добре. В Україні є тисячі людей, які пережили набагато гірші ситуації. Я постійно пам'ятаю про це і намагаюся не скаржитися.

8. Чи відчуваєте ви, що війна змінила вас? Як саме? Чи здивувало вас щось від початку війни в собі (як ви впоралися, залишилися сильними, знайшли натхнення в несподіваних джерелах тощо), у вашій країні, у ваших уявленнях про людство? Чи були якісь прозріння?

На жаль, так. Я бачу, що вже не така весела і безтурботна, як раніше, не так часто сміюся, як раніше. У той же час я знаю, що не можна опускати руки, це наше життя і реальність, і ми повинні продовжувати жити. Я вважаю, що якщо я застрягну з негативними думками надовго, то незабаром настане депресія.

Я вже звикла до цієї реальності і до роботи на передовій. Я навчилась краще контролювати свої емоції. Я стала вдячна за своє життя, і такі прості речі, як прокинутися в своєму ліжку, випити кави та перебувати в мирній обстановці, приносять мені радість. Я захоплююся українськими людьми, вони фантастичні, сміливі, розумні і навіть не думають здаватися (принаймні ті, кого я знаю).

9. Що б ви хотіли, щоб світ дізнався про українців у цей момент? Про українських жінок?

Українські жінки - це скарб України! Вони хоробрі, коли воюють на фронті, вони мудрі, коли підтримують своїх військових коханих, вони добрі, коли допомагають іншим українцям. Українські жінки є волонтерами, жертвують кошти та допомагають іншим евакуюватися; вони достатньо сильні, щоб продовжувати жити, піклуючись про своїх дітей, як матері-одиначки (на жаль, росіяни вбили багатьох наших хоробрих захисників). Наші жінки є справжніми берегинями своїх родин і нікому не дозволять їх скривдити.

10. З якими труднощами доводиться стикатися, будучи фіксером, продюсером історій, людиною посередині, яка може спілкуватися з обома сторонами - українцями та журналістами?

Це може бути складно, тому що будь-яка сторона може звинуватити продюсера, якщо щось піде не так. Найскладніше для мене - це коли ми беремо інтерв'ю у людей, і саме мені вони розповідають історію, а не журналістам. Вони дивляться на мене через спільну мову, і іноді дуже важко передати цей біль і сльози. Ці емоції проходять крізь мене.

11. Чи важко жити в Україні і намагатися достукатися до іноземної аудиторії? Що є найскладнішим аспектом? А найпозитивніший?

З кожним днем це стає дедалі складніше. Новини швидко застарівають, а утримувати увагу іноземців до України стає дедалі складніше. Ми повинні знаходити більше цікавих історій, фактів, доказів тощо. На жаль, Україна не є топ-темою у світі. Іноземна аудиторія сприймає її як "о, Україна... знову!".

Попри все, журналісти закохані в Україну. Вони продовжують повертатися, хочуть працювати тут і продовжують розповідати про те, що тут відбувається. Вони чітко розуміють ситуацію на місцях і роблять все можливе, щоб привернути увагу читачів.

12. Хто ваші WOW-Жінки, які вас надихають?

WOW-Жінки для мене - це ті, хто має достатньо хоробрості, щоб боротися за нашу незалежність на фронті, пліч-о-пліч з чоловіками. Українські жінки, які воюють, отримують повагу від своїх побратимів і не здаються. Вони мене дуже надихають, хоча, зізнаюся, я не така хоробра, як вони.

13. Яке місце чи заняття робить вас щасливішими?

Досить проста річ робить мене спокійною і щасливою: пройти тисячу кроків з чашкою кави в цікавому оточенні.

14. Як, на вашу думку, змінюється динаміка всередині країни, ставлення до тих, хто виїхав, і тих, хто залишився? Чи вважаєте ви, що українці, які виїхали з країни, мають особливу відповідальність перед батьківщиною?

Чесно кажучи, я не думаю, що ті, хто виїхав з країни, мають особливу відповідальність. Це був їхній вибір. Вони будуть жити з цим вибором до кінця свого життя. Ми не маємо права їх судити.

Але якщо ви поїхали, будь ласка, допоможіть хоч якось, хоча б пожертвами, не показуйте нам, українським військовим, світу своє ідеальне життя в безпечному і модному місці. Багатьох це ранить і дратує. Якщо ви питаєте про ситуацію всередині країни, то вона ще гірша: здається, що люди в небойових регіонах майже забули про війну. Для них війна десь "там", далеко від них. Здається, повторюється ситуація конфлікту 2014-2015 років. Так українці не переможуть! Солдати, які повертаються додому у відпустку, бачать, що людям просто начхати на війну. Тим часом українські солдати щодня гинуть на фронті за те, щоб решта країни жила мирним життям. Цивільне населення має бути більш небайдужим і уважним.

15. Як вам вдається робити те, що ви робите, як ви знаходите в собі мужність бути на фронті і що змушує вас щоразу повертатися до своєї роботи?

Я вірю, що я чимось допомагаю, і це дає мені сміливість продовжувати.

Крім того, робота з журналістами - це щось справді унікальне: я ніколи раніше не зустрічала стільки цікавих людей, не бувала в стількох місцях у своїй країні та за кордоном. На цій роботі ти завжди увімкнений і відчуваєш себе в курсі подій; це може бути свого роду згубна звичка.

Ніколь Танг, Эвелина Рябенко та їх команда, які працюють у різних куточках України, показують світові реальність війни росії в Україні! Source: Інстаграм Эвелини Рябенко.

16. Що буде першим, що ви зробите, коли Україна переможе? Про що ви мрієте для себе і своєї родини після закінчення війни?

Плакати.

Я тепер розумію, чому наші діди і прадіди плачуть, коли розповідають про Другу Світову Війну. Вони кажуть, що немає нічого гіршого за війну, і вони праві.

Я не мрію про перемогу, бо не хочу жити в мріях та ілюзіях. Перемога занадто далеко, щоб мріяти про життя після неї. Треба жити сьогоднішнім днем.

17. Де інші можуть знайти вас/вашу роботу? (посилання на веб-сайт, блог тощо).

Мій ФБ: @eveline.riabenko

Instagram: @evelineryabenko

Сайт NYT, де я допомагала збирати історії, подібні до цієї: "Це спосіб життя: Жінки залишають свій слід в українській армії". Мова йде про сплеск кількості українських жінок, які вступають до лав Збройних Сил України та стають волонтерами на бойові позиції.

Це мій профіль у мережі LInkedIn.