THIS INSIDE UKRAINian Heart STORY IS FROM Brussels, Belgium.

* All images and answers in the feature were provided by the WOW Woman, unless otherwise specified.

“I see Ukrainians abroad as a vibrant patchwork, each representing our homeland in their unique way. In my opinion, we all bear a responsibility to advocate for our nation and speak the truth, especially during russia's brutal war against Ukraine, marked by indiscriminate bombings, occupation, and the torture of Ukrainian civilians. I take immense pride in highlighting the contributions of Ukrainian women abroad, committed to helping Ukraine, each making a difference in her respective field and area of expertise. Some women are fundraising, purchasing, and delivering protective gear for the Ukrainian military; others collaborate with prosthetics researchers abroad to support Ukrainian veterans. Some spread the truth about Ukrainian culture on TikTok, while others engage in Ukrainian civil societies in countries like South Africa.

Dr. Olga Burlyuk, a Ukrainian based in Brussels, exemplifies this commitment through her powerful writing, intellect, and razor-sharp wit. Olga doesn’t mince words in her analysis of russian colonial violence and imperial ambitions; she challenges global myths about the russian invasion and Western reluctance to recognize Ukraine's agency. She confronts external pressures on Ukraine to seek “peace” rather than decolonial justice, exposes the problems with explaining Ukraine to Ukrainians living and breathing the reality of direct russian aggression. Dr. Burlyuk is doing her part in the intellectual corners of Europe, ensuring that authentic Ukrainian voices are present and heard in the sea of insidious ‘westsplainers’. I am pleased to see her efforts peer-reviewed and deservedly recognized. I’m also extremely proud to present our interview for the Inside Ukrainian Heart WOW Woman series. Feel free to soak up Olga's wisdom; you’re welcome!”

- Olga Shmaidenko, Founder of WOW Woman.

Professor, Scholar, Ukraine Advocate, Brussels, Belgium

1. Name

Olga Burlyuk.

2. Where is your hometown?

Kamyanets-Podilskyi, a historical center of Podolia region, in western Ukraine.

3. What is your profession/career/title/self-label/designation? What does your average day look like?

I am associate professor of Europe’s external relations at the Department of Political Science, University of Amsterdam (the Netherlands). My job consists of teaching, research and social engagement.

4. What did you study in school?

I studied law at the National University Kyiv-Mohyla Academy (UA) and European Studies at the University of Maastricht (NL). I hold a PhD in International Relations from the University of Kent (UK).

5. What was the journey like to get where you are (in life and career-wise)? Write about some of the achievements that you are most proud of. What was the moment for you that changed your life (in your personal life and/or career?) that set you on the current path in life?

Oh wow, how does one answer these questions?

With regard to my path as a migrant woman in Western academia, I wrote about it in two essays that are published open access and which the readers can find online for free: “Fending off a triple inferiority complex in academia: an autoethnography” (2019) and “A smart hot Russian girl from Odessa: when ethnicity meets gender in academia” (2023). I think these two will give quite an impression of my path.

If the question is more broad, “why academia?”, I guess the answer would be: I have a true passion for knowledge – acquiring, (co-)creating, passing on, disseminating. Always had. So far, I have been able to satisfy this passion through a career in academia. It gives me the freedom to pursue my curiosity and my sense of mission and to do so while working inter-disciplinarily and inter-generationally. This might change one day, who knows.

As for the achievements I am most proud of, hm… I have recently had a conversation with a friend on ambition: how ambition is often limited to professional ambition and, as such, also understood narrowly as some kind of vertical hierarchical advancement or formal acknowledgement. I find this extremely limiting, unsatisfying, unrepresentative of a person’s “footprint in the world” and, frankly speaking, damaging to one’s mental health.

I do not think this interview is the time or the place to speak of my ambition as a person on the whole. But speaking of my ambition in the profession, I try to think of it in horizontal and interpersonal terms. And so a recent “achievement I am most proud of” would be, for example, an email from a former student telling me how my course was the highlight of their exchange semester at the University of Amsterdam and affected much of what they did back at the University of Toronto (focusing their further research on international justice for Ukraine). Or a comment in student evaluations complementing me for my “sense of humor, however dark”. Or the invitation to be interviewed for UkraineWorld podcast and this platform, WOW Woman.

I am also extremely proud of receiving the 2024 Best Article Award of the American Association for Ukrainian Studies for the article “(En)Countering epistemic imperialism: A critique of ‘Westsplaining’ and coloniality in dominant debates on Russia’s invasion of Ukraine” (published open access in 2024) – because of the prestige and the peer recognition, yes, but more so because of the visibility this prize gives to the message of the article and the fact that it was a collaborative effort by us co-authors as four (rather junior) female scholars from Central & Eastern Europe and Central Asia.

6. Advice for other women?

Sleep. Sleep is vastly underrated and hugely important. Speaking as someone who’d been fighting insomnia for years.

7. Where in the world do you feel “tallest” (i.e. where is your happy place)?

By the sea. Any sea, any weather.

8. What extracurricular hobbies are you most proud of? Why?

I would not say I am proud of this hobby in any way, but it’s perhaps a more curious one: I collect tickets. Entry tickets to whatever I’ve done, seen, visited, travelled, since 1998. I have a box full, and I plan to make a giant “wall art” collage of this collection in my home one day. I see it when I close my eyes. You can imagine I am quite upset about the whole digitalization business: actual paper tickets are becoming increasingly scarce, and there is no personality or joy in a QR code, you have to agree.

9. Future goals/challenges?

I am writing a book that is very important to me on a personal level and that I will not tell you anything about just yet. A big future goal and challenge is to see it finished and published.

10. What are (at least) three qualities you most love about yourself and why? What are your superpowers?

I will name three features of the way my brain works (or my “style of brain”, as I recently heard Anne Enright say on The Women’s Podcast) that I particularly appreciate: my thinking in connections and associations, my appetite for observation and genuine interest in people (as a species), and my precise memory (a blessing and a curse!). These are perhaps “superpowers” for a social scientist. In any case, thanks to these, I am never bored.

11. What advice would you give your 14-year-old self? What advice would your 14-year-old self give you in return?

“Keep it up. And remember to have fun.” (both ways)

Although, now that I wrote the above, a memory descends to me: As a law student in Ukraine, I was interviewed for a national legal newspaper once (Yurgazeta, 2007; I went ahead and found my email correspondence with the interviewer!). A large spread, with a photo on the front page, featuring me as “the future of the legal profession” (that didn’t age well, did it?..). And I remember the interviewer being struck by something I said in passing (and in turn him being struck made me reflect on it more seriously, so much so that I remember it to this day):

“Do not limit yourself by the expectations of others.”

I think I might want to say this to a 14-year old me, and in return.

12. What are you reading now? (What books do you gift most and what are your favourite reads?)

I am in the middle of three books right now, I have three shelves of ‘to-be-read’ books waiting (in Ukrainian, English and Dutch), and I have tickets to three “meet the author” events in Brussels in the next few months. I honestly wouldn’t know which books and what authors to feature here! I’ll simply say: as a general rule, read as much as you can, and have books for different moods in mind/at hand.

13. Can you nominate three (or more) women you know who perfectly fit WOW WOMAN description?

Kateryna Zarembo (political scientist and analyst, translator, writer, mother of four and a volunteer with the Hospitallers Medical Battalion), Darya Tsymbalyuk (scholar, artist and creator), Haska Shyyan (Ukrainian writer, translator and poet), Olga Shumylo-Tapiola (counsellor, psychotherapist). Four incredible Ukrainian women who are totally rocking it in their professional and ‘civic’ lives, at home or abroad (or both), and are invaluable members of their respective communities & social networks.

17. Where can others find you/your work (links to websites, blogs, etc.)?

People can follow me on X (@OBurlyuk) and LinkedIn

Consult my page on the University of Amsterdam’s website. Click on “publications” for the links to my academic and non-academic publications, podcasts, and media appearances.

Google Scholar link.

ResearchGate link.

1. Where were you when the russian attack took place?

When Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine started, I was in Amsterdam for work, sleeping on a friend’s sofa, and was woken up by an SMS from my husband saying, “It started.” I knew enough.

2. What was your experience of the day the war started? Where did you go and what do you recall was your plan?

Honestly, I am trying to recall the details now – but I only remember the main strokes.

I remember lots of calling with family in Ukraine.

I remember showing up to teach the 9.00 am lecture. (Yes! Because why not?! Being in shock will do that to you).

I remember being verbally assaulted by a Russian man on the train Amsterdam-Brussels as I was rushing to return to my home-away-from-home – and walking four carriages down the train before I felt safe again.

I remember feeling completely dislocated: I was not only not in Ukraine with my family, and so completely useless to them; I was also not in Brussels where I am based and where I could be of use to someone, somehow, or where people who love me could be there for me. Moreover, I was on the train for a large part of the day – in motion yet completely demobilized, unable even to check the news or contact people due to interrupted signal. I felt grossly misplaced that day. (In fact, for months I had a psychological block against going back to Amsterdam, and I confided that much to my supervisor (immensely grateful to her for understanding!). I switched all my teaching online and worked from home for several months.)

I remember arriving home to find my then 6-year-old daughter heartbroken by the news of her school teacher quitting, which the teacher had dropped on the kids that day, coincidentally, and me having to find it in me to console her about that.

I remember joining a manifestation outside the Russian Embassy in Brussels that night.

You know, these lines above seem completely absurd and meaningless when I think of how that day looked for my family and hundreds of friends in Ukraine. Almost embarrassing. And yet, writing them gave me chest pains for much of the day.

3. How are your family and friends doing? How often are you in touch?

You would need to ask them. I get “some version of the truth” that they share with me, and I know it is gravely edited. They are in Ukraine, continuing with their lives to the extent possible. We are regularly in touch.

More generally: among many other things, the invasion revealed what an immense network I have in Ukraine and abroad, and made me realize that this is not the case for everyone. Any place in Ukraine named on the news with regard to the “theater of war” – I know someone there or from there. Any place in Europe and beyond a friend or a colleague would be fleeing to – I know someone there or from there. I have spent the first months since the invasion, a year maybe, working as a fixer (I learned that this was even a thing much later). As the joke in my circle goes: “Olya. Connecting people.” (I am gambling here on you being old enough to remember the Nokia slogan!)

4. What concrete actions (big or small) have you taken and continue to take to help Ukraine and the Ukrainian people?

Well, since I am based abroad, I join(ed) in the diaspora efforts of all sorts – from interpreting to the arriving refugees and helping to find accommodation, through participating in the manifestations, to collecting Ukrainian books for the local libraries, contributing to social media pages, fundraising and simply connecting people.

Since I work in the “knowledge industry”, as I call it, and Ukraine in international relations is quite literally my area of expertise, I would focus my efforts on the information front of the war: talking to journalists, appearing on TV and radio, giving endless guest lectures and attending closed expert meetings in Brussels, The Hague and beyond. The war revealed the “best kept secret” that I spoke Dutch more or less fluently; I say “best kept” because even I was not aware, let alone my family, friends and colleagues. And so I found myself active in the Dutch and Flemish media spheres for a while, commenting on various aspects of the war and, again, connecting people.

(image depicts the pathways of guided aerial bombs and Shahed drones, launched from russian positions in the south east and north, reaching any and every possible location inside Ukraine. This is the image I often want to show when asked “Is anywhere inside Ukraine safe?” source)

And of course, my primary occupation as an academic leaves a lot of room – places a demand even – for me to engage with the war through research and teaching, “changing the world one student at a time”, as I like to joke. So there is that, too. The war has drastically altered my research plans and agenda, and it is omnipresent in my teaching. I have reflected on this, and I find that it has been both a virtue and a curse: a virtue in that my work provides me with a constant and meaningful outlet, and a curse in that this way the war never stops, it permeates my professional and my private life, regardless of my being physically removed from Ukraine.

But I must say: often small but concrete efforts with tangible effects felt more meaningful than being a “talking head” at the higher public or political level. The latter often felt like speaking into the void. I have an essay in draft on this, with a working title “Engage cannot disengage: where does the comma go?” Hopefully, it is finished and published one day.

5. Do you feel the war changed you? How? Since the start of the war, has anything surprised you about yourself (how you have handled yourself, remained strong, found inspiration in unlikely sources, etc.), about your country, about your ideas about humanity? What have been some of your epiphanies?

I don’t know if the war changed me – or if it created circumstances in which some personality traits had to manifest and be utilized more than others. You know what I mean? “You only know how strong you are when being strong is your only option.” I don’t know who said it, but this line – however cheesy – keeps coming back to me these past 2-3 years. In my case, the invasion started at a time when I had a husband with a severe post-Covid, two very young kids and a new job that involved international commute. So I’d had to be stronger than I ever cared to be. “I am a Ukrainian. And what is your superpower?” I keep wanting to buy that t-shirt!

The war is having a profound affect on me, that’s for sure. “I am not OK”. In fact, I used to send the song by KAZKA under this title to everyone who’d reach out and ask how I was doing. I even had a dedicated slide in my lectures. I imagine only (much?) later in life will I be able to assess the physical and mental health damages, really.

Epiphanies? Maybe a few observations that have been on my mind, in random order.

The duration of war. How long is long, the sense of time, the speed of the passing of time. In history books, we read about “a 16-days war”, “a 44-days war”, the World War I lasting four years and the World War II lasting six, “a 30-years war” and “a 100-years war”… These numbers now gained a whole new meaning for me. I discovered how long 5 hours or 5 days can actually be, or one month, or a few years. Which in turn made me wonder how long is “long” and “long-term”. If counted from 2014, Russia’s war on Ukraine is now almost twice as long as World War II. If counted from 2022, it is now almost half as long. Is that long, very long, extremely long – or not long enough yet? And when world leaders say their countries will “support Ukraine for as long as it takes”, how long are we talking and is there an expiration date? I pose these questions to my students, and it visibly makes them think.

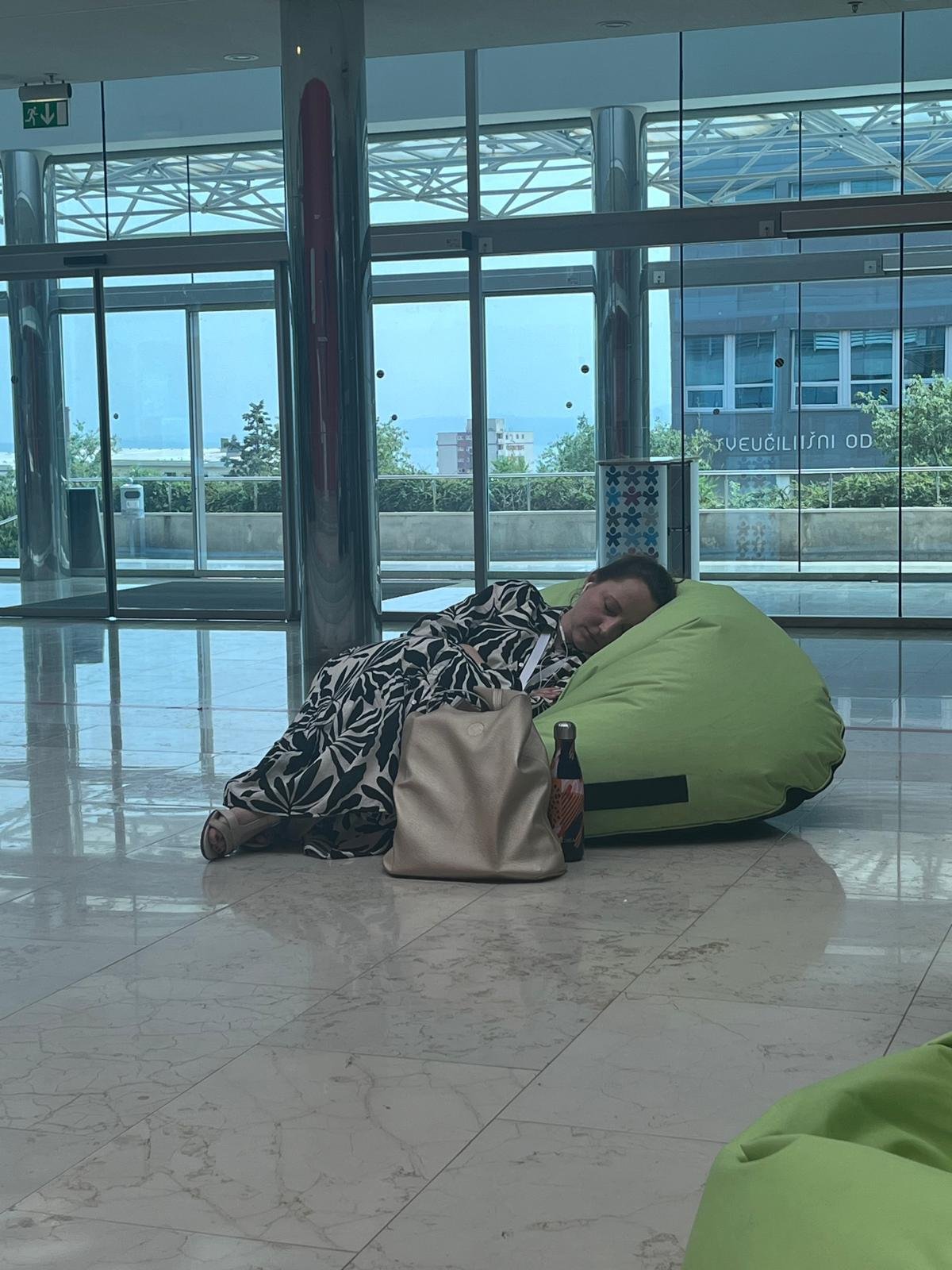

In the images: (1) conferences, talks and the power naps in-between; (2) #sittinglikeagirl a la First Lady of Ukraine, Olena Zelenska, (3) soaking up the EU support for Ukraine; (4) our flag, soaring in Brussels.

Continuing daily life amidst war. The stories of peaceful life or life under occupation during WWI and WWII in novels and memoirs always seemed confusing and, frankly, un-believable to me. And here we are. “You only live once” and “Live like you may die tomorrow” transformed from a metaphor to a daily practice. Normality – in anything – embraced as a form of resistance in itself. The fragility and the liminality of the physical, emotional, intellectual distance between the battlefield and the home front, between the material and the ideational. The porosity of the “defense walls” one might be building for oneself.

Being a mother, or any woman/person with care duties, through a major crisis, in this instance a war. I once asked my mother how she had experienced and remembered the collapse of the Soviet Union. She paused to think and responded, “Olya, I had a baby and a toddler. It went right past me” (or something to that effect). When the full-scale invasion started, I had a baby and a first-grader (and my husband was on long sick leave, too). On the one hand, this simple reality did not allow me to immerse and engage as fully as I’d want to (that is, 24/7 and not merely the 14/7 I’d been pulling off). The public engagement of millions of women is constrained daily by their care duties, in many cases withdrawing these women from public life more or less entirely; this is nothing new, feminist literature has said a lot on the subject. It also did not allow me time to process anything at all – neither as it was happening, nor afterwards (hence, as I wrote above, it remains to be seen what the effects of the war on me truly are). On the other hand, caring for my family, my children, being with them – right there and then, on their time, not mine – provided the necessary grounding, a source of joy and hope. A lifeline, really.

Finally, a sense of humor as a vital trait. I was talking with a close friend and colleague recently, and she said, “Olya, it is remarkable that you’ve preserved your sense of humor through these awful circumstances.” I paused to think about what she said and rebutted, “Actually, it is the exact opposite: My sense of humor preserved me through these awful circumstances.” I genuinely believe that’s the case.

6. Do you want justice for Ukrainians?

I do want justice for Ukraine and Ukrainians, and that involves international responsibility and accountability of the Russian state and collective responsibility and accountability of the Russian population – the good, the bad and the ugly, regardless of one’s individual sense of guilt.

And here I want to share a somewhat ironic story, linking back to your earlier question on my “path” and “how I got where I got”. As I mentioned already, I studied law. I was a complete public international law junkie, and I was quite good at it, too: I was Ukraine’s Best Speaker in the 2006 Philip Jessup International Law Moot Court Competition, Ukraine’s National Champion in the 2007 Jessup competition (with the Kyiv-Mohyla team), and ranked in top-8 teams and top-50 speakers representing Ukraine in that year’s International Rounds in Washington, DC (USA). I should have those plaques somewhere… And then I sat down (or more likely: went for a walk in the park) and thought to myself: “I want to do something meaningful for Ukraine, for Ukraine’s future. I am that generation that was the first to go to school in an independent Ukraine in September 1992. I have a mission. And what use am I going to be if I do international law?! It’s a joke! I will probably end up teaching somewhere!” And so I decided to commit myself to Ukraine’s European integration instead, went on to pursue a degree in European Studies and write a PhD thesis on the European Union’s support for rule of law reforms in Ukraine. Fast forward 15 years – and the state of Ukraine is litigating against Russia in nearly every international court and tribunal that exists. Even in those designed for individual citizens’ complaints (I am referring to the European Court of Human Rights here). And it is sometimes my study peers and fellow Jessup-junkies who represent Ukraine in those trials (some even reached out to ask if I were available to join a team!) And I teach European studies. The irony is not lost on me, I promise! At least Ukraine’s European integration is progressing, too. Phew.

7. What do you want the world to appreciate about Ukrainians and Ukrainian women in particular?

A lot, but let’s keep it down to two.

In 2019, I published an article “Imagining Ukraine: From history and myths to Maidan protests”, co-authored with my dear colleague and friend Vjosa Musliu. In the article, we analyze conflicting narratives on what Ukraine is and what it should be, and how past, present, and future are used to imagine contemporary Ukraine. In one of the narratives, “Ukraine as Ukraine”, we quote Les Poderevyanskyi, a famous Ukrainian writer, who said in an interview once that Ukraine does have a unifying national idea: “Fuck off!” (Yes, there is a “fuck off” in a published peer-reviewed academic article of mine…) Honestly, if you think about it, that aptly captures Ukraine’s history and Ukrainians’ spirit in two simple words, and obscene words at that. Just leave us alone. Just let us be. Centuries of resistance to invasion and occupation (from Russia and others too, lest we forget). “The state is theirs, the country is ours”. Intergenerational trauma going way back and “refreshed” in almost every generation. I am afraid the extent and the contemporary effects of these are not (fully) comprehended in the world (arguably, not even in Ukraine itself).

The other point concerns women – in Ukraine or anywhere, really – and the role that strength and ingenuity of women play in collective survival in times of acute crisis. I had the pleasure of attending a book talk with Nino Kharatishvili, a Georgian-German writer, a few years ago, and in talking about her latest book set in Georgia of the 1990s, she remarked how the society has survived exclusively thanks to the creativity of women – in finding food, in finding clothes, in finding heat, in giving kids a childhood, in keeping men afloat, and so on. I remember exclaiming in my head, “Oh my god, yes!”, and I keep returning to this idea in the years since. Creativity, ingenuity, resourcefulness of women as the source of lifelines don’t get nearly enough credit.

This photo is from 2004. I am pictured in the orange coat, marching with fellow students during the Orange Revolution, alongside thousands of other Ukrainians. For 17 days, we peacefully filled the streets of Kyiv in a powerful stand against our chronically corrupt government. Together, we stood for and brought about change, sparking a movement that would go on to shape 21st-century geopolitics.

8. What is it like to live outside the country right now and keep connecting to your family and loved ones inside? Can you please describe to those who can't relate to this on a personal level?

There is a sort of dissociation going on, which is a dangerous mental health development but is perhaps inevitable when one is based abroad. Because here there is no war. Everything continues as usual. People plan their four holidays a year. And complain about workload and prices. And make 5-year-plans. And expect you to make 5-year-plans, too. And the work is there, as usual. And the coffee-machine-chatter, as usual. All of it: as usual. Only nothing is as it was before for you. Often, I have this out-of-body experience during interactions with people and catch myself switching on/off a different (side of my) personality. Darya Tsymbalyuk and Bohdana Kurylo wrote powerful autoethnographic essays on this, published in the special forum “The responsibility to remain silent?” that I co-edited with Vjosa Musliu (2023). And Oksana Potapova, a feminist scholar based in London, wrote beautifully and with utter honestly about this on her social media accounts. I recommend you check these out.

With regard to connecting to one’s family more generally: migration is a major rupture in itself, and war adds as a whole new level to that. Yes, we know that no two people ever live through the same event in the same way, even if they are perfectly in synch. However, in situations of migration, the distance (physical, temporal, social, emotional, …) is structural and can be huge. And then the war comes in with an ax. What can I say? They are living through the materiality of this war, and I am not really. It requires that much more love, empathy and understanding to “stay tuned” and not to let this push you apart.

9. What do you feel is the right approach to eventually encourage all the people who left the country (~6 Million Ukrainians) to eventually return?

I am convinced that no one can tell anyone what the right thing to do is. Every person takes decisions in light of their unique combination of physical and mental health, family situation, financial situation, profession and skills, where in Ukraine they are from and whether there is even anything to go back to, etc. Noone can truly step into another’s life and advise – let alone dictate – what is right.

That is not to diminish the fact that the demographic losses Ukraine has suffered, is suffering and is yet to suffer are on a grave scale and truly irreparable. An old friend of mine used the word rozsypalysia in a conversation we had on this: українці розсипалися по світу. The English translation would be “Ukrainians spilled/scattered around the world”, but it does not do justice to the undertones of the verb my friend used in Ukrainian. I discussed this with a French colleague at an academic conference recently. He asked me about reparations and what Russia might need to do to set things right by Ukraine (your regular conference reception question, clearly! #dissociation). And I tossed an entire list of irreparable damages at him – material and immaterial – that can never be compensated. Demographic losses would be one of those. It is truly heartbreaking.

To be entirely honest, however, I try not to think about the long-term effects of the war really. My mind keeps returning to the premise of Lina Kostenko’s book “Notes of a Ukrainian madman” (Записки українського самашедшего): the main character (my age) had a mental disorder in that – unlike regular humans – he actually thought about the news, what it meant and constituted, and it overwhelmed and consumed him fully, all the way to an attempted suicide. I am doing my best to remain a ‘regular human’ on this.

10. What will be the first thing you’ll do when Ukraine wins? What are your dreams for yourself and your family after the war is finished?

I will take my kids on a long summer holiday in Crimea, like I did every summer as a child and young adult. Either we do a 12-hours-by-car journey – pick a watermelon directly from the field somewhere in Kherson – arrive in Yalta after dark, rolling down the serpentine road from Simferopol. Or we do a 24-hours-by-train one – buy some snacks through the train window in Koziatyn and then Dzhankoi.